August

28

I wake from a dream in the middle of the night and scratch out this note to help me recall the dream in the morning:

Dancing ladle/tef >silver>gold…alive

In the morning, fully awake and far from the dream state, I use my note to draw back as much memory of the dream as I can. I recognize that the memory of the dream is nowhere near as “substantial” as the dream itself, more a simulacrum of the original. But remembering is better than not, so I work my sketchy note into a narrative of sorts. Here is the text of the dream I wrote in my dream book.

I see a ladle hanging in midair as if held by some unseen hand. It's moving about, twisting this way and that. As I look into the Teflon bowl of the ladle, it changes to bright silver. Its movements are ever more a graceful dance, balletic even. As I watch, I see the silver change into bright gold. I realize the ladle is alive! I am awestruck.

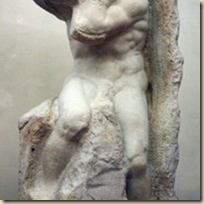

I am aware to the point of pain how inadequate my written text is in relation to the dream experience itself. As text, it fails to capture the palpable reality of the dream, the awe in realizing the ladle was alive. Like my camera capturing David,[1] the resulting two-dimensional images were only reminders of what I experienced with the living sculpture itself. Even with uninterrupted moving images (film) I have seen, the framing was so focused, that the enveloping contextual reality within which I experienced David was missing.

It is common to refer to a dream as “my” dream. This is similar to the proprietary aspect of capturing a photograph that is the subject of Susan Sontag’s masterful critique of photography.[2] The “appropriating” she decries applies as well to how we relate to the dream. We appropriate the dream and call it “mine.” As I have written before,[3] when we photograph, we milk reality for its truth.[4] Likewise, we tend to “milk” the dream for our own ends, our own needs, our own intentions.

I realize that milking the dream to serve our conscious intentions is a perdurable activity that is not going to change—its history is too long, its utilitarian value too embedded, its “obviousness” too obscuring of any other approach. I know that most anything I say here is going to fall on the ubiquitous “deaf ears” of the standard approach to dreams, which leads to seeking meaning, interpretation, and analysis, all of which leads “away” from the dream itself.

Nonetheless, I want to look at the dream differently.

The dream presents itself to us. It comes as a visitor. Perhaps instead of “capturing it,” we might treat the visitor as a guest. Then we would be host to the dream. I’m thinking of Baucis and Philemon, and how they invited the beggars in, something no one else in the town did. While the townspeople who rejected the beggars paid a steep price (drowning in a flood), Baucis and Philemon were rewarded. The disguised gods (Zeus and Hermes) made it possible to grant them their wish: to die entwined together as an everlasting tree.

Freud made it a fundamental principle that dreams are disguises, disguises for the dreamer’s unconscious desires. Jung disagreed and felt the dream was “just so.” But Jung did emphasize in many ways that what was crucial was to welcome the dream as a guest. But contemporary attitudes toward the dream tend to forget this. The common mode is to “use” the dream for its utility value in serving the ego.

The dream, however we recall it, comes to our experience already crafted with exquisite precision, or impressionistic flux, or fleeting but impressive impact, or eerie vagaries. Consciously, we could produce none of this. So how are these experiences we call dreams crafted?

We don’t know. Probably the best answer is that dreams are crafted by something other, certainly something other than our consciousness. We might argue that at some point brain science will unlock this mystery and we will have a more complete picture of how the brain crafts dreams. Still, it will be how we relate to these experiences we call dreams that will be crucial.

The dream exhibits artisanal forces at work in the making of the dream, already worked, already crafted, already smithed into the forms we see by an unknown dreamsmith.

We can approach the dream as critics and form an opinion of it, try to discern its meaning, attempt to assess its value, and otherwise try to understand it. But as Baudelaire observed, “the only proper criticism of a work of art, is another work of art.” In Psyche Speaks, I wrote of a dream that pictured me leafing through Jung’s Memories, Dreams, Reflections. A piece of paper fell out and when I looked at it, there was written, poem-like:

The poem wants a poem

The dream wants a dream

Notice how this dream shifts the emphasis from the dreamer’s desire, to the dream’s desire. This dream had a powerful effect on me because it radically shifted my own way of working with my dreams as well as those of others—wherever that is possible.

Jung’s “active imagination” way of working with dreams, now made clear with the publication of his Red Book, is clearly one way of satisfying a dream wanting a dream.

I think that almost any artisanal approach to a dream carries this same spirit. As an example, I have lately taken up approaching my dreams poetically before textually. What I mean is that I steep myself in the memory of the dream and while in this experience I write a haiku.[5]

Here is the Haiku I wrote following the dream:

The Teflon ladle

turned bright silver, then bright gold

dream ladle: alive!

In my experience, working on a dream haiku within a kind of meditative state, brings forth spontaneous memories. For example, in this instance, what came is the memory of Kandinsky’s reflection I had quoted in Psyche Speaks:

Everything that is dead quivers. Not only the things of poetry, stars, moon, wood, flowers, but even a white trouser button glittering out of a puddle in the street…Everything has a secret soul, which is silent more often than it speaks.

At once I knew what to do. I went to the kitchen drawer and fetched the Teflon ladle. This everyday mundane object now took on that quality of Kandinsky’s trouser button. Could my consciousness see into the ladle as deeply as the dream? One thing I know: I can no longer pass by anything as if it is a lifeless object. When things become “alive” in this way, it is not the rational mind that will be moved; it will be the artist-soul that will want to dream this aliveness into new forms.

This I believe is a key to understanding the principle of eros that underlies the nature of the Coming Guest. More about this in the next post.

[1] See the previous blog post on “Dreamsmithing.”

[2] Susan Sontag. On Photography. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1977.

[3] See my “Afterword” to Jeff Jacobson’s My Fellow Americans… Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1991. The relation between the photograph and the dream has yet to be fully essayed. This afterword was my initial attempt to do so and remains my favorite piece of my own work.

[4] I used J. Robinson’s 1658 lines as an epigram: “My wished end is, by gentle concussion. the emulsion of truth.” In exploring the etymology of emulsion, I found that emulsion derives from the root melg-, which means “to milk” hence its relation to photography. How this changed when photography became digital and lost its connection to the emulsion of film, I will explore later.

[5] Haiku is a Japanese form that is not readily transferred to English. The standard English equivalent is a tercet (3 lines) with 5, 7, and 5 syllables. The “art” of haiku is rich beyond what I can articulate in a brief note. But I encourage your exploration of this form as a way of “distilling” the essence of a dream. I don’t mean to limit this approach to haiku, but I do like the way the form forces one to an unusual effort. More on this later.